By Atena Kamel

The body and the archive

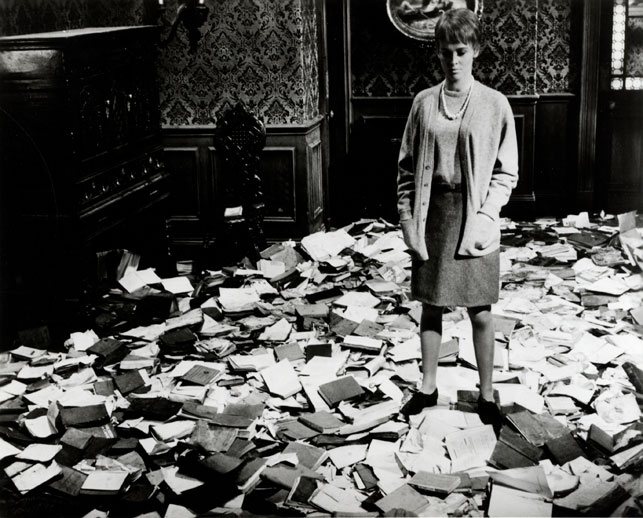

“Fahrenheit 451” by François Truffaut, 1966

Death can be interpreted as amnesia. It appears that there would be no archives without the possibility of forgetfulness. Archiving is our attempt to prevent or delay the inevitable: the fragility of connections and their permanent loss. Otherwise, archives become more important in authoritarian systems. A challenging battle to control the archive and the reconstruction of collective minds is going on in such countries. One side uses its resources and power to limit and channelize information and facts in order to maintain its being while other side has undergone such suffering and repression that seeks its survival in making it conspicuous and evident. Narrating oppression and recording it in history is part of the healing process and hope for change. As a result, people’s archives get their strength and power from the slippery place between life and death, and thus they are powerful and effective. Life and death are defined by the body, and the body is a living archive.

Francois Truffaut tells the amazing story of the world in the movie Fahrenheit 451 (1966), when reading books is a crime, and firemen are not supposed to put out the fire, but to set the books on fire. 451 degrees Fahrenheit is where the book paper catches fire and burns. In this situation, book lovers decide to become the books themselves. Everyone memorizes the text of their favorite book, which is prohibited by law. Although the precious books are burned by the firemen of the regime, they survive in the bodies of book lovers. Book keepers take refuge in the forest and wait for a moment when someone wants to read them, someone is interested in listening to what they can repeat. Every book is a moving body and everybody has become a moving book. But the body is mortal, and it is the librarians’ mission to ensure the survival of each individual archive through repeated chains of transmission. A group of people dealt with maintaining an archive of books which represented physical and emotive records which are transferred from one body to another. The book can live in different bodies. It can survive because of the connection with its listeners; Listeners who are willing to listen to the whole book, parts of it or quotes from it.

Archiving of books in bodies is an interesting and metaphorical tale. (Palladini & Pustianaz, 2017: 14)

Firstly, if a body can become an archive, it is simply because the body is already a living archive. Our body can keep records of assaults, violence and humiliation. “To share a memory is to put a body into words” (Ahmed, 2017: 23). A body that has become a book won’t alienate itself from what it has piled up in memory and yet is able to intertwine the book with its own history. Secondly, it can be said when an archive is tied to a body, it is tied to the history of that body, i.e. it is tied to the changes, transformations, events, memories and death of that body. The archiving of books or memory in the body is related to the life span of that body. Embodyment brings about risk and instability and instability and risk necessitate archiving.

Resistance and archiving

An Archive is associated with loss. It is a part of the whole and therefore it should be understood in its context. An archive is a sign of the lost. A subtle indication of what we mean by its entire representation. Archive primary purpose is to not let things, feelings and resistance be forgotten and interpreted otherwise. It aims to intervene in the construction of our collective memory. Archives that are rooted in loss represent loss. It is as though what was lost gave its power to speak and show to the archive. Mourning is a part of our affective archive.

The ‘Dadkhah mothers’ (the ‘justice-seeking mothers) are the scene of affective encounters both in real life or on social networks. A place where strangers or those who didn’t know them before the incident, see their pain, desperation and suffering. These mothers find each other, visit each other and introduce themselves with the names of their children. In Iran, over the years, they have created certain social networks regardless of the hardships. They have attended numerous events and anniversaries related to their loved ones regardless of arrests and prosecution. Moreover, the personal belongings of their loved ones were lost, their homes were not safe from attacks, or they were afraid that their only possessions would be stolen. Because of this, their personal memories, photos clothes, and belongings were usually moved to a safe place outside home, outside the family and sometimes outside the country in the form of an archive that is being added to.

Many of those who participated in Mahsa/Jina Amini protests 2022 were arrested, beat up or tortured. They sent their personal photos of gatherings or their tortured bodies to their acquaintances abroad to be preserved and kept. The Investigative Committee of the Detainees was formed outside Iran in the fall of 2022 and by introducing an e-mail as a means of communication and information created a valuable archive of the detainees’ status upon Jina uprising. Besides, private photos and videos of activists, detainees or those who were suspected of being detained in parties and private spaces with their friends were inevitably erased and if possible, a copy of it was sent abroad. This way, we could have a rich archive of films, photos, notes and articles from the protests of September 2022 and later on in diaspora.

Sholeh Pakravan, Reihaneh Jabari’s mother stated in an interview with Asoo website:

“I am a total archivist, I still keep Reyhane’s childhood dress. I still keep my children’s favorite toys. They are so important to me that I brought them to Berlin. This is who I am, but obviously my motivation for Reihaneh upon her release was to come and see the process she went through. I wanted her to see that her presence filled our home. I thought she would come and I could tell her that this is the archive of your life when she was gone. Unfortunately, this wish of mine did not come true and the story that should have remained very private and was only for us, was shown to the whole world… I published the book [How a Human Can Become a Butterfly: A Mother’s Tale of an Execution] and now I feel liberated after the release of this movie. After 15 years, I have been sleeping without sleeping pills for a week. My world has changed. I am just seeing Berlin. I tell people around me that Berlin has great parks. I didn’t really see them before. I wasn’t living. I just passed days. I took full responsibility of Reihaneh, but the lawsuit will not end until the execution is completely eradicated in Iran. The last gallows should go to the museum so that our future generations will understand that there used to be system that hanged humans at the dawn with the sound of morning Azaan. they would die two to three minutes later. their sufferings would end and yet the survivors would suffer until the end of their lives, and their lives would be hell. As long as the execution machine in Iran is convicting death sentences and people in prisons are awaiting death gallows while their families are under agonizing stress, the justice seeking will not be complete…”

There is an important part of the archives in exile. And the semantic gap between exile and archive is interesting. Archiving is a kind of connection, a living connection of names, generations or narratives, while exile is a kind of seclusion or “archive seems to suggest a kind of connectedness – biographical, generational, narratological – and exile, a relinquishment of the security of a known past and of the knowability of what is to come” (Dubow, Steadman-Jones and Babbage, 2013). The association of these two indicates the possibility of an unexpected crisis on the safety of archive. An archive in exile is highly volatile so that it can accommodate unexpected crises i.e. endangered lives or losses in a safer place. An archive in exile seems to move the home outside the home. Home here refers to both family and homeland especially when being at home means fear and terror. Archiving in exile is not novel, it is a long-standing and repeated practice in history, from Judaism and Christianity to medieval political systems and dictatorships as well as fascist regimes.

Exile is not immigration. Exile is accompanied by ostracism, a kind of rejection which, according to Foucault, is the result of all kinds of mechanisms of absorption and inclusion; The methods that define acquaintances and strangers. All members of a nation or even a group are not included and relied on equally. The reliability of members can fluctuate based on specific criteria. The same scoring and validating criteria are applied to the mechanism of exclusion. As a result, although rejection refers to outside of the society, it is also considered a difference within the society. Foucault paid special attention to forms of exclusion in absorption procedures. His early works focused on external disciplinary mechanisms and later on self-discipline and aspects of biopolitics. Many researchers, inspired by Foucault, addressed the archives. For example, James Given (Given, 1997) discussed Inquisition and its archived documents in the Languedoc region of France in the Middle Ages and has highly inspired Foucault’s early works.

Just as the inquisitors in the Middle Ages created their own archives, governments today are also in the process of creating their own archives. Historians have found similarities between confessional and inquisitional methods inside and outside the English-speaking world. For example, Mark Gregory Peg, who investigated the Inquisition in the Lauragais region in the south of France between 1246-1245, shows how the questions of the inquisitors transform everyday life into spaces, times, sounds and lights that no longer could be taken for granted where ordinary life stopped (Staub, 2013: 76). Writing or talking about oneself in such an environment is the most obvious form of government control over life. Same thing is sometimes broadcast in the state media which belongs to the government archive and is against people’s archive.

Writing journals, diaries and biographies in exile is also a recognized form of archiving. There numerous examples in Persian literature: “Names of exile” by Mirza Agha Khan Kermani, “How a person can become a butterfly” by Sholeh Pakravan, “Days on the Road” by Shahrokh Maskoob, “Dar Hazar” by Mahshid Amirshahi are among these works. These works do not only include personal feelings and even public emotional states at the individual level in a shared history. Perhaps it can be claimed that all those who are involved in the work of archiving and producing knowledge are concerned about the mobilization, reorganization of forces and the general activation of emotional states. Individual or private feelings are not left out, but the production of such archives happens to be those who may be able to transform private feelings into public effects, whose purpose is not to only show social or political written stories, but to finish the unfinished work of the archive itself.

Feminism and the archive: from personal to political archives

Feminism is praxis in the sense that it is an operational paradigm for our way of being in this world. Becoming a feminist, according to Sara Ahmed, is “how we redescribe the world we are in. We begin to identify how what happens to me, happens to others” (2017: 27). The annoying and rejecting practices and patterns are revealed to us and our sensitivity provoked. We entitle ourselves to be disobedient toward these practices be it in private or public. Feminists’ lives are an archive of rebellion and defiance or as Ahmed puts it, our bodies are our personal archives. A Feminist is someone whose body is encased in the established gender order and has come into contact with the outside world. A feminist is someone who has taken wounds and started to think about these wrong practices and has tried to give meaning and name to the feelings that their body goes through. So, they started to archive situations and events. When this body comes across other similar archives, whether in the form of living bodies or books, stories, and narratives, it realizes how similar it is, what a correct analysis, what a proper naming, and thus it can narrate a personal archive impersonally and politically.

Some become more impersonal archives, for example, the bodies of Dadkhah mothers, a body with bullet holes in its back, and a body that has lost an eye. These bodies too lost something or experienced painful and terrifying that were not meaningful to them. A more general look at the courts overseas dedicated to historical cases are remarkable examples of the importance of archives that rely on the testimony of the victim’s families, former prisoners and biographies and inmates’ memories.

In Egypt after the fall of Mubarak, when people were in the streets for months, women were the targets of widespread sexual violence and gang rape. A vast and organized violence that aimed to keep women away from the public. The Supreme Council of the Egyptian Armed Forces called them shameless women who are “not like your daughters and mine.” In the book “Revolutionary Life” (2021) by Bayat, he says that nothing was as effective as the presence of these women on the television screen and their public and brave stories of what happened to them. The public scene saw numerous controversial debates and for the first time in Egypt the body and their sexuality and their position in public were put to question in a referendum and eventually in a historical turn in June 2014, sexual harassment entered into Egypt’s penal code. This time, the bodies of the abused and violated women were able to reread its memory loudly and contribute to change.

Let’s go to Argentina where some feminists have linked the glorious “Ni una menos” movement to the historical struggle of mothers and grandmothers in Mayo Square. This feminist movement revived the lineage of Mayo’s mothers and established new links between the types of oppression that are applied to women’s bodies. Riots create a strange kinship. An important debate that took place in Argentina was that the men who were in charge of the secret and terrible detention centers of Buenos Aires were creating a similar repressive atmosphere at home and among their family members. Their daughters showed their solidarity and resistance against oppression by attending the “Ni una menos” march. Such an intervention in the memory of present time in the words of Veronica Gago (2020: 103) manifests a timeline that has begun with the efforts to fight back Argentina’s military dictatorship and engulfs the memories, archives and stories of the suspense and terror of those women: The link between Ni una menos and Mayo Square Mothers.

Archives for the outcasts and those who do not fit into the current order is a tool for remembering and visibility. In order to maintain balance between the support provided by the current situation or any situation, archivists should be responsible for waking the marginalized groups in the society. It is obvious that political elites need information systems and media control to maintain their position. Because political power is in control of archives or even more strongly the control of collective memory. Documents or individuals other than government archives are the same essential elements used in the Nazi regime in Europe, apartheid in South Africa, dirty war in Argentina and genocide in Cambodia.

The crimes of the past have increased the sensitivity towards the archive in favor of accountability, social justice and pluralism of ethnic and gender groups. Reviewing the archival literature, Randall Jimerson, in his article “Archives for All: Verbal Responsibility and Social Justice” (2007), enumerates four ways archives can contribute to the public interest: “to promote accountability, open government, diversity, and social justice” (Jimerson, 2007: 256).

Archives, both in the sense of material places where objects and reports of the past are kept, and bodies are volatile spaces that show us and generate forms of resistance. They are not fixed, non-social or timeless spaces, but dynamic spaces that connect the past, present and future. As a result, archival knowledge production should be understood in the spectrum of time. Archival knowledge goes back and forth in time, just like how something new makes us go over the past and think about the future. The archives of protests, movements and revolutions should be read not to review the events based on their chronological arrangements, but in relation to today and the gaps and breaks that are rooted from the dominant narrative.

The rise of Jina is an unfinished narrative that can be questioned from a new perspective each time; The relationship between Jina uprising and women’s demands, women’s movement and gender minorities, Jina uprising and ethnic minorities and oppressed nations, Jina uprising and the issue of execution, Jina uprising and the university, suspensions and expulsions, Jina uprising and sexual violence in detention centers, etc. Jina uprising managed to unearth old issues such as injustice against women and ethnic groups and the abolition of the death sentence once again in a wider range, and from now on it will be evoked and questioned in the light of every political situation. Archiving plays an important role in clarifying the limitations and possibilities in these situations, bringing the unfinished issue before our eyes so that we can make a claim, relate and move forward.

Refrences:

-Bayat, Asef (2021), Revolutionary life, The Every Day of the Arab Spring, Harvard University Press, London

– Dubow, Jessica, Steadman-Jones, Richard & Frances Babbage (2013), Introduction, Parallax, 19:4, 1-5

– Gago, Verónica (2020), Feminist International: How to Change Everything, translated by Liz Mason-Deese, Verso

– Given, James B. (1997). Inquisition and medieval society: power discipline and resistance in languedoc. Cornell University Press.

– Jimerson, Randall C. (2007), Archives for All: Professional Responsibility and Social Justice, The American Archivist, Vol. 70, No. 2 (Fall – Winter, 2007), pp. 252-281

– Palladini, Giulia, Pustianaz, Marco (2017), The making of our lexicon, In Lexicon for an affective archive Intellect Books. January 29 2024, P 10-19

– Staub, Martial (2013) The Hidden and the Naked: Heresy, Exile and the ‘Truth’ of the Archive, Parallax, 19:4, 74-83

– Ahmed, Sara (2017). Living a Feminist Life. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv11g9836