This chant was first sung by a group of students at the Farzanegan (intelligent) High School in 2000. The poor-quality video and blurred screen, coupled with the students’ sonorous voices, recall old school days and call for critical minds to ask a few questions. It is not clear precisely which quality of the past can revive smells, voices, and ambiance once one sees an image or watches a video. What feature in this frame gives the audience, in this case, me, the possibility of existence among other students, reckoning with her past, re-imaging her present, and reframing her future? With the image, I jump into my past and become a student chanting among my fellows. I asked another student if she had ever been affected by an image and how an image knots me with her body, making a line between my past, her present and our future. My friend gave me a puzzled look and continued chanting. I am in the middle of the school hall and singing with others. Yet, I am detached from the chant. I wonder how, by seeing their image and listening to their chant, an avalanche of memories, voices, smells, principals’ yelling, and our terror in the face of seeing them at school came flooding back to me. It seems an intermemorial ceremony for me in which my visual, auditory, and kinetic memories are knotted together to revive a related experience. I didn’t want to bother my friend by asking too many questions. Still, again, I queried whether she knew how her chant could radicalize other students, imagining themselves in a just alternative future. I kept asking if she knew that what they were singing would become canon for two-decades-later students. My friend turns to other friends and loudly sings:

Tomorrow one hundred stars will grow

And falls from the sky

Tomorrow a bright and warm light will come out of the pitch darkness…

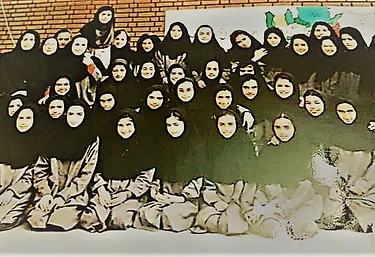

The chant is being sung at the Farzanegan high school, which belongs to the National Organization for the Development of Brilliant Talents. It is a high school where those talented students are supposed to be reproduced for the country’s promising future. However, the chant content is against the ideology of Islamic education! Or it means otherwise for us today. The school staff aimed to create a world where in which they could make the most of the Islamic student’s labor. Conversely, the students were chanting for a revolutionary, promising, free-of-any-ideology world. They didn’t understand, though. I jump out of the school, the video, coming back to my own body, sitting at my desk and looking at them from afar. I see their triumphant look, full of youthfulness. I see they are hand in hand, reclining on each other’s shoulders.

What encourages them to chant such a revolutionary song in the ideological educational context of the Islamic Republic? Singing this chant when today’s rebellious students demand a livable and just life knots multiple times with each other. My dim and distant school memories flood back when they shout, “Tomorrow, a bright and warm light will come out of the pitch darkness.” To whom did that “tomorrow” belong? The chant echoed throughout my forty-year-old body. I am thrown again to my high school. Somayeh. We were about to sing a political chant. Those dumb religious teachers never understood what the chant was about.

Yet, I remember our bodies in terror, lest they interrogate us about why we chanted that. I recall another day when the principal summoned and interrogated us about why we didn’t say “down to the U.S.A” at the schoolyard. These memories mingle with those students’ bodies in the video. I suppose they are in the school hall, between the chemistry lab and Namazkhaneh.[1] Like us, their noses might have been filled with the odor of socks. These students are lucky if they are asked officially by school staff to chant. Otherwise, they would be interrogated for chanting a political song. I stare at the video again, reflecting on how these students have called the next generation’s radical imagination without knowing it in advance. I reflect on how past times can radicalize the future. I am not that student anymore. Neither are Farzanegan students the same people. They might even be on the streets these days, with their sons and daughters, chanting the anti-government slogan: Jin, Jian, Azadi.

by Haleh Mir Miri

[1] Namazkhaneh is a place mainly located in schools and governmental organizations where individuals must go to say prayers. It can be synonymous with a chapel.