This call is from Evin Prison

A letter from Sarvenaz Ahmadi to Sepideh Rashnu- November 2023, Women’s Ward of Iran’s Evin Prison.

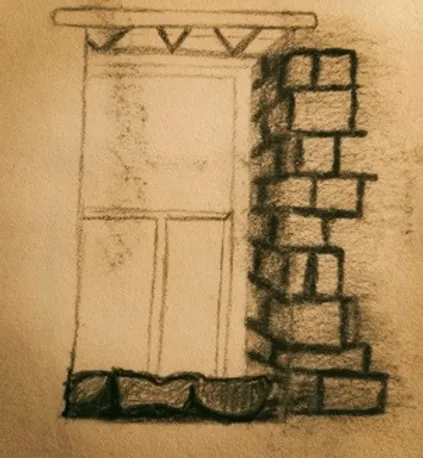

Tanide⸻ Dear Sepideh! Your letters and poems are finally here. Today is November 23, and I am here to get fresh air. I am writing this to you believing that my letters will eventually reach you. I just wanted to touch base and share how I feel. What confines this approximately ten-by-twenty room, and the act of getting fresh air into a prison, is repetition. An inmate esteems anything that bears the essence of the “new.” When you send me a letter, it feels like you have sent “new words” to me. It appears as though those tall poplar trees behind the area where we go to get fresh air are now adorned with new coats. At times, one might be petrified of becoming a mundane object, fading into obscurity and being forgotten; particularly, in those innocent eyes…

[A female voice message from Evin Prison: This call is from Evin Prison]

When sending a letter to a prisoner, the essence of the collective “we” materializes within that letter. Sometimes, when someone asks if I need anything, I’d like to request letters, fragments of Arabic poets’ imaginations, and a collection of eloquent pens. Dear Sepideh! It has been seven months now since I have been here, and I must spend five more of these seven months; when I recall Shams Langrodi’s poem, Ghasideye Labkhand-e Chak Chak, especially when he writes that “now I have forgotten life, and I barely remember how children look like” the yearning squeezes my heart. Always, there is a child in your proximity who is enduring suffering and, at the same time, displaying resilience. When I was free outside of the prison, there were Afghan children, children laborers, and those grappling with mental health and cancer. Here, I witness the children of female inmates, as well as those originating from war zones, whose images are broadcast on the prison’s television. It was Vahid outside, and here is Ronika with me. I should convey this information to their mothers, emphasizing the importance of being honest with their children. When a child inquiries about their mother’s return, an educator should speak plainly to them. For instance, the mother should say she will return home in five more birthdays. There are many cement walls between my hands and the war-wounded hands of the seventy-five-year-old children of the Middle East. Imprisonment is indeed an experience of loss, but it is also a rigorous exercise in holding onto what remains in your fist. These days, I am reading a book regarding the social work of children in war. It serves as a valuable resource to teach children in war—those whose noses are filled with odours of burned bodies and gun power— not to collapse or what should they do when they find themselves petrified by a profound sense of fear, dreading to be buried under the ruins once again. Being buried might seem intolerable for any shoulders; let alone those children who even do not know how to write a border; no children are born with their boundaries. I wrote that imprisonment is an experience of loss. Every passage through the prison door is an experience of loss. Being sent to jail results in the loss of your loved ones, and it’s during that period that you come to truly appreciate the depth of your love for them. At this moment, you come to realize that spending time with your friends, standing on Bam-e Amir Abad, eating your sandwich in the middle of winter, and gazing at the highway may seem trivial, yet it was both enjoyable and hilarious. At this juncture, you realize that this act of standing has transformed into your distant, sweet dreams. Those who have been released from prison and have returned share the same sentiment, signifying that upon release…

[A female voice message from Evin Prison: This call is from Evin Prison]

…you will once again experience the loss, recognizing how your fellow inmates in the cell were near and dear to you. Otherwise, when you are free outside of the prison and you want to bum a smoke, there are no fellow inmates to tell you, “Wait for me to join you!” On the very first morning upon your release, when there are not forty people around to respond to your “Good morning,” you may feel forlorn. You have lived with these forty people throughout the day, battling the most exhausting issues with the most unbearable individuals. When you are free, you will not spend as much time with people, as you have to go to work and cannot see them throughout the day. A distinct sense of loss arises when you find yourself still confined in prison while other inmates are released, eliciting a range of conflicting emotions. Sometimes, a prisoner is exiled, and you experience a feeling that I call “the shortening of the heavy prison ceiling.” At times, you find yourself within the confines of the prison while someone outside passes away. Even more demanding is discovering that those comrades have crossed borders not native to them, choosing to leave the country.

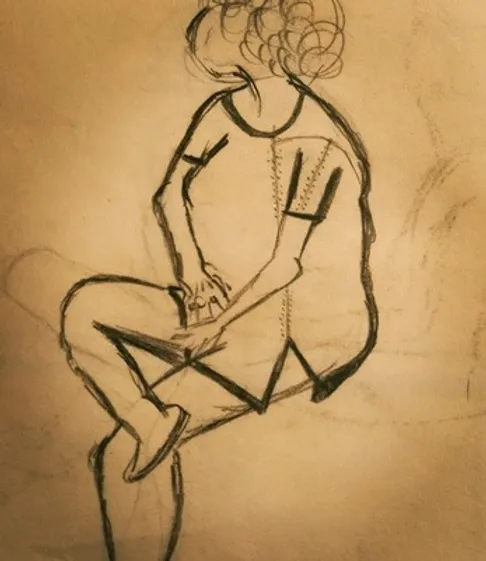

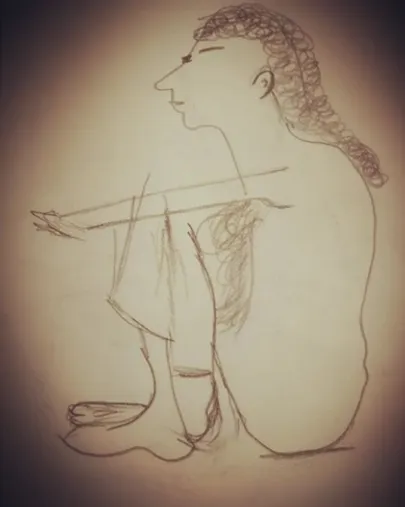

Losing things that you cannot cope with is noticeably challenging. Even within the confines of prison, one can attain accomplishments. Some of my most profound friendships have been formed behind bars. I am convinced that sharing challenging experiences solidifies profound friendships. Perhaps it’s because most people here haven’t been indifferent toward others, and I believe it’s precisely for this reason that they are present here in the first place. They are like a book, and I wish I could send each of them to you to read. They are like chants. I wish I could send them to you to sing. Getting fresh air in the evening is similar to strolling in a cypress grove. Cedars stand side by side, walking shoulder to shoulder. Here is the image: one cedar is engrossed in a book, while the other is either knitting, crafting leather, or delicately smoothing a piece of wood with sandpaper. Another cedar, adorned with curly leaves and a presence spanning almost six years, shows genuine concern for our modest garden. She harbours no expectations other than nurturing the growth of daffodils. There is another cedar, seventy years old, with the strongest roots and juniper-like leaves. At roughly specific hours, she always appears. While carrying her lush branches in her pockets and smoking, even though she has been here for almost four years and still has another four to go, she seamlessly declares herself a communist whenever faced with new arrivals. Perhaps, she has another starry sky in her eyes apart from this ten-by-twenty of the sky we have above while getting fresh air. In brief, she bears a striking resemblance to the cover of your book.

The birds frequently arriving at this prison often experience foot problems. It might be caused by the barbed wires surrounding the prison. Their chicks sometimes tumble into the prison’s yard, perishing well before two days…

[A female voice message from Evin Prison: This call is from Evin Prison]

These cedars, however, have steadfastly embraced their social commitments for years on end. In moments of fear, they have consistently pressed forward with unwavering determination. They have extracted life out of each hideous brick of the prison’s walls. Birds boast about their freedom to soar through the skies, while cedars, on the contrary, take pride in their roots and resilience. Another cedar sleeps on the upper bed above mine every night, having not eaten anything for a few days. Each time, instead of saying ‘Goodnight,’ I tell it, ‘my comrade neighbour! Goodbye until tomorrow night,’ and we laugh together, shedding a few tears. Prison is loaded with paradoxical emotions.

Dear Sepideh, you who kindle the red flames of our morning breathe! How even in some hours we transformed into readers of each other’s letters. Deep down, I know that I found the holiness of words in you, well before I knew you were a poet. To be honest, discovering that you’ve endured Tehran’s crowded seven in the morning subway commute to reach work by eight o’clock deepened my feelings for you. Working claims many hours of our time outside the confines of the prison. I did not work many days in my life. Yet, I cannot possess my days here until the evening unfolds its four hours. The discipline of school and university years, followed by the routine of work, has accustomed me to alienate myself from morning until evening, yet I am changing it. I have attempted to paint a picture of life beyond these walls for myself. I finished translating a book and it needs a revision now. I have learned to make leather bags, and I could sell some of them. I teach English, and eventually, I am supposed to learn Arabic. I still do not dare to read those books on the art of fiction writing. I mostly read poems. When the smoking room is empty, I go there and immerse myself in reading poems. When I read out loud, my voice reverberates. Echoing my voice fills me with an overwhelming delight and this is what I do in my me-time. When I was free outside here, I used to go to the cinema, often alone or occasionally with one or two others in the afternoon Showtime. I would either go to the theatre alone or treat myself to the French Confectionery, trying to gradually discover myself. However, once I found the entirety of myself all of a sudden. It was a revolutionary time, and I sensed that I was no longer an alien to myself. In those few moments, I found myself in an ocean of people where I was unable to see the end. These people came to chant their lives. It was only in those few moments that I thought for a while it was over…

[A female voice message from Evin Prison: This call is from Evin Prison]

I said to myself that I had lived what I desired. It was the last Monday of the month. You are a drop of that ocean, Sepideh! I have written your piece of poem here on this board:

When branches in the weaves of wind

Had lost birds and nest

Tree said to itself

It is only one feather; I wish there was just one feather left…

You are that left feather from any soar, You Sepideh Rashnu! The blaze of the sincere morning.

Sarvenaz,

November 2023, Women’s Ward of Iran’s Evin Prison