Tanide’s introduction:

Iran’s contemporary history is a history of struggles and oppressions. From monarchist regime to the Islamic regime, there have always been bodies revolting against all these regimes of oppression and discrimination in Iran. Among them, women and non-binary individuals and communities have been at the forefront of resistance and struggles for liberation and bodily autonomy. The transgender community in Iran has been among the marginalized communities whose very existence has been medicalized, overly sexualized, discursively and politically discriminated against and so on. The following narratives, that are retrieved from Rang Gallery Instagram page and website (www.rangallery.com) and translated from Farsi into English by Tanide Collective, are the narratives of discrimination against trans* individuals and how compulsory hijab has impacted them in many ways. Compulsory hijab and its many unjust impacts are mostly discussed with regard to cisgender women. Of course cisgender women are impacted by compulsory hijab; however, other non-binary and queer and trans* bodies are also equally impacted by this barbaric law. On March 8th, 2025, and while celebrating the longstanding struggles and resistances of women and non-binary bodies in Iran, we find it very crucial to echo and underscore the narratives of struggles and resistances of trans* bodies as depicted in the following narratives to both raise awareness to these multifaceted struggles and to show the entangled nature of oppression and resistance on and by bodies whose appearances, sexual orientation, identities, politics and subjectivities deviate from the heteronormative society. The following text is the translation of one introductory article on the issue of compulsory hijab and trans* community in Iran as well as five narratives around this issue by four trans* individuals. We hope that in the following weeks, we publish all the narratives in English and on Tanide.

Happy March 8th and happy the resistance of all the revolting bodies in Iran and the world.

Compulsory Veiling and the Transgender Community in Iran

From: A group of Trans* activists.

No. 1: A Reflection on the impact of compulsory hijab with narratives from Trans* individuals.

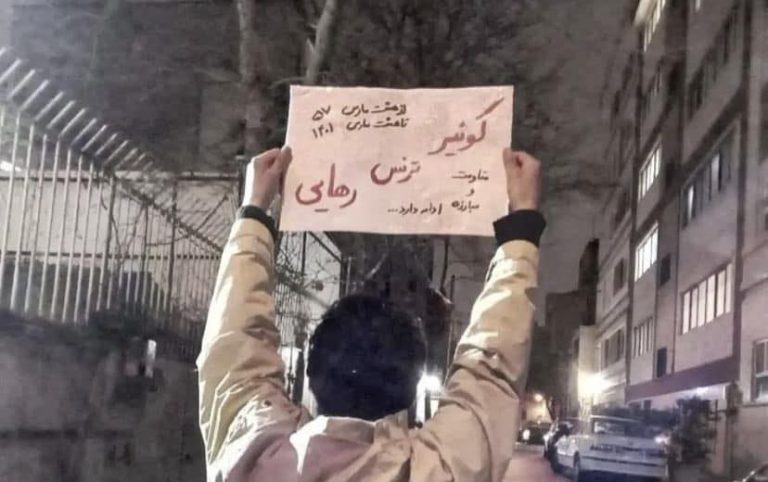

March 8th (17th of Esfand) every year marks the anniversary of the first public protest by women in Iran against mandatory hijab. This protest—or more accurately, a feminist struggle—has continued for as long as the Islamic Republic has been in power.

Within this historical struggle, there have also been scattered efforts to draw public attention to the impact of mandatory hijab as a form of systemic discrimination, particularly on the trans* community in Iran. However, a significant portion of the discourse—and consequently, feminist activism against compulsory hijab—has primarily focused on the situation of cisgender women, often excluding trans* individuals.

The following article examines the effects of mandatory hijab on trans* individuals inside Iran. To this end, it first reviews the penal code related to mandatory hijab and its history, followed by media reports and evidence. Finally, it presents firsthand accounts from trans* individuals in Iran on how compulsory hijab has directly impacted their lives.

It is important to note that throughout this text, the term “trans*” is used to refer to the broader transgender community. For definitions of other terms and concepts used, one can refer to the terminology guide on news coverage standards published by the Trans Journalists Association.

A Brief Look at the History of Mandatory Hijab

The first statements about compulsory hijab emerged after the victory of the Islamic Revolution, on March 6, 1979 (15th of Esfand 1357 in the Iranian calendar). In a speech at the Feyziyeh School in Qom, Ayatollah Khomeini declared: “Islamic women must appear in public with hijab, not with makeup. Working in offices is not forbidden, but women must observe Islamic hijab.” (Ettelaat Newspaper, Issue of March 6, 1979).

The day after this speech, female employees in government offices and public institutions who did not observe Islamic hijab were barred from entering their workplaces. Of course, the prosecution and conviction for the crime of “cross-dressing” may also apply to cisgender individuals who wear clothing not traditionally associated with their assigned gender. However, what makes this accusation particularly significant for trans* individuals is that clothing (when chosen freely) serves as a means of expressing gender identity and, consequently, reaffirming social gender. This self-expression can reduce the psychological vulnerability of trans* individuals. However, under the threat of such convictions, they are largely deprived of this possibility.

This issue becomes even more critical in light of the gender segregation in Iranian schools, the minimum age requirement of 18⁸ for legal gender affirmation through family court, and reports of various forms of conversion therapy being practiced in the absence of legal prohibitions. These factors create an environment in which trans* children and adolescents are placed in highly vulnerable conditions, with mandatory dress codes playing a significant role in their struggles.

It is worth noting that during the legal process for obtaining medical approval and receiving a court-issued certificate for gender-affirming surgery, an individual may request a document known as a “clothing permit,” which is issued by forensic-approved psychiatric authorities. However, due to the bureaucratic complexities of the certification process, this permit is not granted to all trans* individuals. Furthermore, as reported in the testimonies later in this article, even possessing such a document does not always prevent initial acts of violence by law enforcement officers.

Given these circumstances, the question arises: what legal position do trans* individuals who are unable to obtain legal gender affirmation hold under the mandatory hijab law?

To answer this, we must first examine Article 638 of the Islamic Penal Code, which not only mandates hijab for women but also criminalizes any “forbidden act” committed by any person in public spaces. The determination of whether an act is forbidden is left to the discretion of the presiding judge. Based on this legal authority, a judge may convict any trans* individual of the crime of “cross-dressing.”

Although “cross-dressing” is not explicitly defined as a specific crime in Islamic criminal law, it is classified under the broader category of “forbidden acts” within Article 638. This means that if any individual appears in public wearing clothing that does not correspond to the gender assigned to them at birth, they may be prosecuted, convicted, and punished under this article.

As a result, trans women face a dual burden: they are required to wear the mandatory hijab even after legal gender affirmation, and before or in the absence of such legal recognition, they risk being convicted of “cross-dressing.” Similarly, trans men are not only subjected to the mandatory hijab before legal gender recognition but are also at risk of being prosecuted for “cross-dressing” during this period. Additionally, non-binary individuals who are denied legal gender affirmation are continuously at risk of prosecution and punishment under this legal framework.

Article 638: Anyone who publicly commits an act deemed forbidden in public places or thoroughfares shall be sentenced, in addition to the punishment for the act itself, to imprisonment from ten days to two months or up to 74 lashes. If the act itself is not legally punishable but is considered offensive to public morality, the individual shall only be sentenced to imprisonment from ten days to two months or up to 74 lashes.

Note: Women who appear in public places and thoroughfares without observing Islamic hijab shall be sentenced to imprisonment from ten days to two months or fined between 50,000 and 500,000 rials.

At first, not all trans* individuals succeed in obtaining forensic medical approval and a certificate from the family court. Due to the binary perspective that shapes the legal definition of gender, non-binary individuals are not legally recognized and are therefore ineligible for a legal gender affirmation certificate. Additionally, trans* individuals who experience gender in ways that do not align with traditional dysphoria narratives or who, for any reason, do not wish to undergo the surgeries required by the family court, are denied forensic medical approval and, ultimately, the right to legal gender affirmation.

In response to such statements and actions, on March 8, 1979 (17th of Esfand 1357), women organized a large-scale protest that lasted six days and drew thousands of participants. Despite facing various reactions, the demonstrations ultimately led to the temporary repeal of the mandatory hijab requirement in government offices and institutions.⁴ However, this outcome was short-lived. Following Ayatollah Khomeini’s directive to then-President Abolhassan Banisadr, from July 5, 1980 (14th of Tir 1359), women were once again barred from entering government offices and institutions without Islamic hijab.

Ultimately, the Islamic Penal Code (Ta’zirat) was passed on August 9, 1983 (18th of Mordad 1362). In its section on “Crimes Against Public Morality and Family Duties,” Article 102 formally mandated Islamic hijab in all public spaces. This marked the point at which dress codes in Iran became legally enforced. Later, in the revised Islamic Penal Code of 1991 (1370), this legal obligation was reiterated in Article 638, and it has remained in effect to this day.

Mandatory Hijab and Trans Individuals*

To understand how mandatory hijab affects trans* individuals in Iran, one must first examine the legal text itself and then analyze how it is enforced—through media-reported cases and direct personal testimonies.

The revised Islamic Penal Code, passed on July 30, 1991 (8th of Mordad 1370) and approved by the Expediency Council on November 28, 1991 (7th of Azar 1370), includes Chapter 18: Crimes Against Public Morality and Ethics.

Based on this legal framework, trans men before legal gender affirmation and trans women after legal gender affirmation are required to comply with mandatory hijab laws. While this fact holds true, the impact and consequences of mandatory hijab on trans* individuals extend far beyond this legal requirement.

The Islamic Republic of Iran operates under a binary and essentialist view of gender.⁵ As a result, legal gender affirmation is contingent upon undergoing gender-affirming surgeries as required by the family court. According to Article 4 of the Family Protection Law, jurisdiction over this matter lies with the family court. This court issues a certificate of legal gender affirmation only after the individual has undergone gender-affirming surgery, as verified by forensic medical authorities.

—

Part Two: Arian’s Story – A Trans Man’s Perspective

“Being forced to bind my chest with elastic bandages, making it difficult to breathe in the summer, was also a form of mandatory hijab for me.”

The following is a collection of firsthand accounts from trans* individuals detailing their experiences with Iran’s discriminatory mandatory hijab law. These narratives also describe encounters with various forms of violence—both from law enforcement officers and the public. Trigger warning: The following accounts include experiences of violence, including sexual violence.

Arian – A Trans Man:

Many cisgender women I have met do not fully understand the experiences and lives of people like me. They assume we have an advantage when it comes to avoiding mandatory hijab, but our realities are far more complex and different from such assumptions.

I have always refused to comply with mandatory hijab. From my teenage years onward, people constantly stared at me—so much so that I became terrified of their gazes. To avoid hearing their comments, I would always wear headphones. Beyond that, I was repeatedly subjected to unwanted touching and sexual harassment on the street. It got to the point where I didn’t leave my house for three months.

For a period, I had no choice but to comply with mandatory hijab in order to feel safer. But this stripped me of my identity entirely, pushing me into extreme feelings of self-hatred and other overwhelming negative emotions. During that time, I coped by escaping into my imagination, picturing myself in different situations just to avoid confronting reality.

Additionally, instead of having access to gender-affirming healthcare (such as a mastectomy), I was forced to bind my chest with elastic bandages—which made breathing unbearably difficult, especially in the summer. To me, this too was a form of mandatory hijab.

I have often heard people say that wearing mandatory hijab makes them feel invisible. I have also felt invisible countless times—it was painful. But at the same time, under so much pressure, I sometimes wished I could truly be invisible, to have no body at all…

—

Part Three: Arezoo’s Story – A Trans Woman’s Experience with Mandatory Hijab at Isfahan University of Art

On my first day at university, during registration, I was pulled aside and told to accompany the security officers! When I asked why, they responded that I had to go with them for violating the hijab regulations! With my family’s intervention and after being misgendered, they eventually let me go. However, all the security personnel and administrative staff treated me harshly and violently. They even threatened to cancel my enrollment if I didn’t cut my hair and change my appearance! Since I was familiar with the legal framework, I ignored their threats, but this first day of university caused me immense distress, anxiety, and trauma.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit and classes moved online, I was able to continue my education more easily. However, when I returned to campus in my sixth semester, I was constantly prevented from entering different faculties due to my lack of hijab. They frequently and unnecessarily demanded to see my student ID. Despite all these challenges, I made it to my eighth semester—only to face even stricter hijab enforcement. During this time, university security was constantly monitoring me.

In my eighth semester, I was told to take a two-to-three-year leave of absence and return home or take online courses so that I wouldn’t physically be on campus. I was even threatened with expulsion. Desperate, I offered to comply with the mandatory hijab rules by wearing a headscarf and manteau, but they refused, saying that because of my “special circumstances,” I wasn’t allowed on campus even with that attire. Afterward, they denied me access to most university facilities and student rights—and they even confiscated my student ID!

One of the university’s cultural affairs officials had a particular issue with me and, with the help of the psychology department, continuously caused me trouble and hardship, barring me from entering most faculties. Eventually, they forced me to sign a personal waiver stating that if anything happened to me on campus, the university would not be held responsible. Only then was I permitted to attend classes in secret—yet even then, my name on the class lists was always marked with a disciplinary warning.

—

Part Four: The Story of Nim-Rooz – A Non-Binary Person, from the Metro to the Women’s Ward

Trigger Warning: Contains distressing content and transphobia

I am a non-binary person, but under the laws of the Islamic Republic, I am misgendered and classified as a woman. While I personally do not associate gender with clothing, my personal choice is to wear clothing traditionally associated with men. I have always fought for autonomy over my body and the right to choose my own clothing, and I have also faced the consequences of that fight.

I remember one time when I boarded the so-called “women’s” carriage on the metro, a woman gave me an angry look, silently telling me that I did not belong there. I often try to ignore such looks and comments and stay where I am. However, when I got into an argument with a morality officer in the metro over refusing to wear the mandatory hijab, that same woman stepped forward and defended me—even though she had previously looked at me with hostility and superiority!

Such looks, along with accusatory comments branding me as a “predator”, have been so frequent in the women’s carriage that once, just to escape them, I entered the so-called “men’s” carriage. But the reactions there were even worse and more violent because they saw me as an easy target for sexual violence, and that time, I was severely harassed and assaulted.

Staring, mistreatment, harassment, accusations, and other forms of violence have come not only from the morality police and government authorities but also from ordinary people—both in public and in prison. I remember sitting in a park and hearing passersby say loudly, “Look at that! Is it a man or a woman?”, followed by laughter. Or in prison, once in the women’s ward, some fellow inmates—whom I didn’t even know—were gossiping about me because of my clothing, spreading the false rumor that I was trying to “spy” on them. Meanwhile, I was struggling with severe psychological distress, to the point that even looking at my own naked body was unbearable for me.

Additionally, in prison, the behavior of prison guards and officials toward me was always inappropriate and violent because of my clothing. A prison inspection officer once told me, “You make me sick! When you stand in front of a mirror, don’t you feel disgusted by the way you look?” I responded, “No, in fact, I enjoy it! Because I am exactly who I want to be—not what you have forced me to be!” The conversation ended in an argument and violence.

I also remember how a guard, the moment he saw me, angrily shouted, “Look at this one! Why do they look like this?! Who even let them in here?!” When I replied that my choices—including my clothing—had brought me here, he grabbed the edge of my shirt and, turning to the prison doctor, said, “Doctor, check this one out! I think they’re one of those!” The prison doctor then asked, “Why do you dress like this?! Are you trying to say you’re a man? Do you have a mental disorder?!”

These are just a few examples of the countless experiences of discrimination and violence I have faced because of the mandatory hijab, which also serves as a tool to oppress my gender identity. Throughout my life, I have been subjected to violence and harassment from both the government and society. One of the most painful aspects of this, however, has been the lack of support for my fight against forced hijab and dress codes—not just from people around me, but even from the media and public figures who, in discussing the struggle against compulsory hijab, fail to mention trans and non-binary people like me

—

Mandatory Hijab and the Trans Community

🔸Part Five: Sheida’s Testimony – A Trans Woman’s Encounter with University Security

“Until you wear a chador, I will not let you enter this university!”

Several years had passed since my gender-affirming surgery, and at the suggestion of some friends, I had started providing guidance and support to other trans individuals, sharing my experiences and offering advice. Because of this, a relatively large number of people had my contact information.

One day, a woman called me, introducing herself as a university professor. She invited me to attend a seminar at a university as an honorary guest speaker to talk about trans experiences. I accepted the invitation and, on the appointed day, dressed entirely in black, wearing black shoes, black dress pants, a long black coat reaching below my knees, a black scarf, and a black shoulder bag.

As I arrived at the university entrance, the security guards stopped me and asked for identification. I explained that I was a guest speaker invited to the seminar. However, one of the security officers fixated on my outfit and said, “Your coat has slits on the sides, and your legs are visible!”

I pointed out that I was completely covered in black and responded, “I’m dressed entirely in black! My coat is loose, and my pants are fully covering me. I find it strange that, as a man, you have such predatory eyes to even notice this!”

This sparked an argument. The officer stood his ground and insisted, “Until you wear a chador, I will not let you enter!”He kept pressuring me, and I kept refusing.

Eventually, the university president, the professor who invited me, and several other faculty members arrived. The situation became so chaotic and tense that it was beyond anything I could have imagined.

Then, they brought out a faded, filthy chador that reeked of stench—I have no idea where they found it! They tried to force me to wear it. At first, I refused, but after half an hour of pointless arguments, the professor and the university president pleaded with me to give in—just for the sake of the 300 students waiting to hear me speak. They asked me to briefly put on the chador for a few steps while entering the building, then remove it once inside, just to silence the hardline security officer.

I wanted to turn back and leave the seminar, but I realized that with so many guests and students present, it would be disrespectful. Against my will and under duress, I reluctantly agreed. I threw the chador over my shoulders and, as soon as I entered and walked a few steps away from the security officers, I removed it and proceeded to the seminar hallwith the others.

After the event concluded, as I was leaving through the main entrance, the same security officer was standing there. Holding the crumpled chador in my hand, I threw it toward him. But as I was stepping out, he kicked me hard from behind, making me stumble forward toward a table nearby. I almost lost my balance and fell, but I managed to steady myself just in time.

I turned around and swung my bag at him a few times, lightly hitting him. This escalated into a scuffle! He grabbed my headscarf and ripped it off, while hurling insults and obscene slurs at me.

The students started screaming, booing, and protesting, and soon a crowd gathered around us. Once again, I was held up for nearly an hour until others intervened and the situation somewhat calmed down.

I wanted to call the police, but unfortunately, the professor and others discouraged me, saying that it would be pointless—it would only harm me and the university’s reputation. They said, “They will never take your side. The authorities will side with security and claim you must follow university regulations.”

That day was a terrible experience for me, and after that incident, I refused to attend any more seminars or conferences.