Writing about Painting, Prison, and Lived Experience

Nazanin Mohammadnejad, an independent leftist activist and feminist, answered these questions in a conversation with Tanideh: Where did the idea of your paintings come to your mind, and what is the relationship between paintings, memories, places, and feelings in prison and outside of it?

Tanide’s Introduction⸻ The idea and experience of “being” in places are different from each other. It is possible to imagine a “place” without being present; conversely, one can be in a “place” whose image and objectivity are not identified. A constellation of senses, emotions, experiences, and even previous narratives of a place always create existing and subsequent images. Our subject-bodies are moved from one place to another by images and people’s narrations. Within this circulation and displacement, something of the kind of non-lived experience, but felt experience, is constructed. It is as if our feelings, which are immaterial and not visible, attach to the materiality of a place or transform from what we had mistakenly felt before. Through this combination of immaterial emotions, images, and narratives, one can move to a place like a prison and imagine its atmosphere. An “experienced” place for some people, and an “imagined” place for others. Probably the first images for those who have not experienced it should be something like this: A place surrounded by chains and fences… with iron doors… and high cold walls. A scary and complicated space with a feeling of constant anxiety and fragility. Later, while those images occupy one’s mind, other questions arise. For example, you might ask about the quality of the experience of being confined in a certain space for different people. How do they turn a day into a night? How do they separate work hours and leisure, or time at all? Or whether this separation is all about labour as defined by the neo-liberal marketplaces outside the prison? How does it feel to be trapped and incarcerated in a place for a long time? How do you feel this time is passing? The answer to these questions will be possible only through imagining and then through conversations with those who have experienced it. One has to be either in a place and experience it or have heard the experiences of “others.”

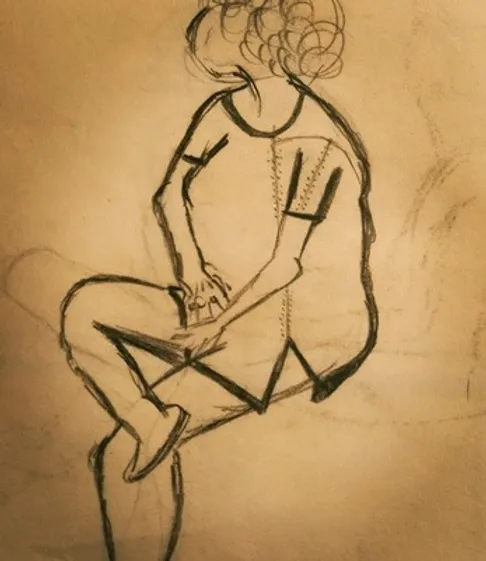

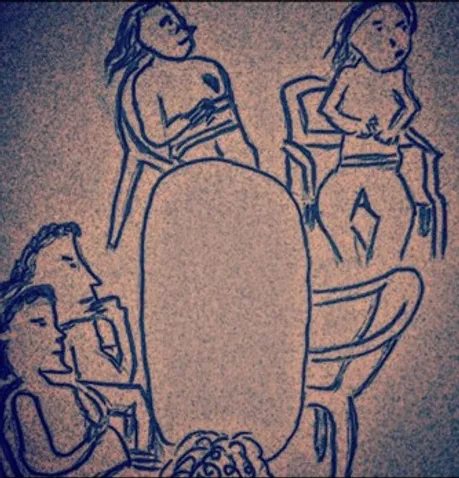

Encountering the prisoners’ artwork, recorded memories or narratives can bring the atmosphere and feelings experienced in prison from unconsciousness to language and significance. The works resulting from these conditions knot the body of the imprisoned person to what she has seen and/or felt and then to the imagination of her audience. With this in mind, Tanide interviewed Nazanin Mohammad -Neghad about her paintings, released on her personal Instagram page. These paintings opened the conversation, which are Nazanin’s experience from the Women’s Ward of Evin Prison between January 2021 and February 2022. Nazanin is a women’s rights activist. At the age of 19, she migrated from the south of Iran to Tehran to continue her education, which is when she got to know feminist groups and leftist activists. She studied social sciences at Tehran University. In 2019, Nazanin was detained for two months due to her activities in the field of women’s rights, and she was then imprisoned in the Women’s Ward between January 2021 and February 2022. The paintings are the result of her imprisonment and are unique in terms of their special relationship with the environment, other prisoners, the prison itself, and time. In them, there is a loud silence and a kind of heavy lightness. A contradiction woven into the texture of simple forms but strongly affected by the space draws the audience’s gaze outside the frame of the paintings. Dense emotions go beyond the image and throw one into the experience of Nazanin and others from prison. The entanglement of anxiety, resilience, hope/despair, small and momentary joys, silence and isolation simultaneously create a unique atmosphere yet one that is heavy and dull. Nazanin first published the paintings on her Instagram page. We asked her to tell us about the initial ideas of these paintings, sharing her experiences about time and place in the jail with us.

Following you will read Nazanin’s answer to one of the long interview questions, the full version of which will also be available on Tanide’s website in the future.

Nazanin Mohammad Neghad⸻ No matter how hard you have striven to gain knowledge about prison or imagine it, you will eventually conclude that most of the things you have seen and understood have been new and unpredictable. You asked me where the idea of prison paintings came from. I would say that female prisoners have been creating artworks and doing sports activities in a form of tradition over the years of their imprisonments in the Evin Prison’s Women’s Ward, to overcome their challenges and for the sake of their sanity. I was sent to Evin Prison’s Women’s Ward at beginning of winter 2021. Upon that entry, I saw many women knitting colourful yarn to make clothes for their loved ones. It simply seemed sheer beauty to me. They were creating something out of their incarceration that might be inherited from other female inmates’ generations. Those generations had understood how to tackle their lives in jail, yet be survived and also be alive. They used to teach each other how to knit different patterns. It also happened that they were knitting while listening to the news outside. There were those fabulous frames of life in prison. Should you look at this frame from afar, you will see how spectacular the scene is. Well! You say “yes” to life, and this is an affirmative way of living.

Knitting was the first artistic activity I learned in prison. I made relentless efforts to learn it and even turn it into permanent entertainment. And eventually, I gave up on crafts, realizing that I love watching them more than doing them. I was seeking an artistic activity that I could relate to more. Other handicrafts such as mosaic, rug and carpet weaving, and leather embroidery were among the popular activities of the Women’s Ward, which did not attract my attention. Prisoners would make creative artwork with these activities. However, I would like to point out that there was usually a direct relationship between the creativity of the works and the cost of their production. The wealthier prisoners are, the more they were able to produce. After all, prison is part of a bigger society where class issues exist. Among the artistic activities that existed in prison, painting and drawing were not of the prisoner’s interest. But, between two women who were in charge of handicrafts, one had some experience in drawing. Once I learned she knew how to draw, I proposed that she teach us it. She delightfully accepted, and thus, we start drawing with charcoal. Of course, there was already a carpet design class, but few people participated in it. The drawing class with charcoal continued for several sessions and three prisoners, including me, participated until it was stopped when COVID-19 hit the prison again. It didn’t continue since we lost our appetite for it after that.

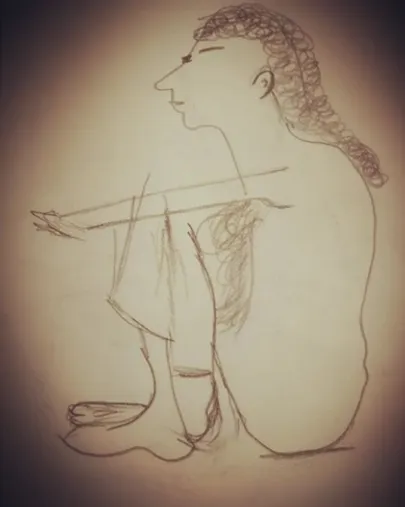

You are a real person, I painted you in the prison yard. I was at your proximate distance and drew your sketch while you were in a world of your own. I don’t like to reveal your real name. I am now sure that you were each of us when, without any intention, we took refuge in a secluded corner, which was difficult to find. I saw myself in you when you took pills to escape reality and slipped down the ladder and burst out laughing; and now, I see myself in you more than ever. When you had the anxiety of not being liked and being forgotten and you heard completely reasonable answers from us, I saw the cause of my anxiety in your face, and I removed it from my face to know myself in another way; and about that night when under the light of the moon, in a confused and drunken state, you insisted on telling the story of your sleeping from the time before marriage, and we were struggling to make you remain silent because of your serious mental and physical condition. Did your desire to tell that story have anything to do with the time you showed your roommates a family photo and one of us pointed at your husband’s picture and asked, “Is that your father?” And you said with a thin and conciliatory bitterness, no, this is my husband, and later you reminded us of the dull memory of that mistake with indifference. Maybe the difference between you and me was that you didn’t want to dig an inner cave towards other caves from your circumstances and you only desired to talk more about your situation in that spot. My heart becomes heavy, and my pulse beats faster, when I feel that a person whose feelings are moved significantly within a certain place and in the light of the passage of time will never forget the magical memory of that place. It is bizarre, isn’t it? That despite emotional and physical intimacy in prison, the individual anxieties of a person, there, as a volcano erupts, from the depths toward visible edges; and now other faces, like yours, can fit in the width of my empty head.

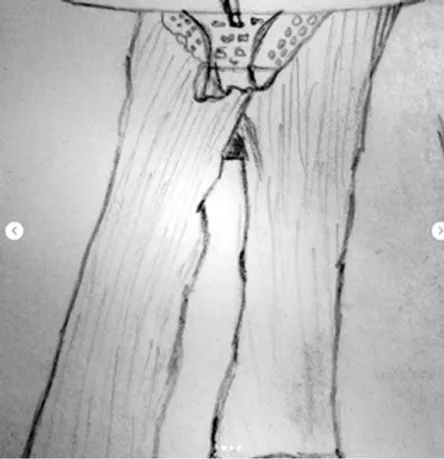

I didn’t intend to learn technical drawing. I simply did not have any motivation, and to be honest, I did not have enough confidence in doing it. I wouldn’t draw that much so I did not have experience. I rather desired to work solely. I was also looking for a way to overcome my inevitable introversion in prison. Those dull evenings in addition to my strong desire for writing history, narrating and recording everyday life — which were the underlying reason why I didn’t like other artistic activities — encouraged me to follow drawing in my own style. To borrow my sister’s description, I should say my drawings are primitive and deformed. Yet, each one of them is a combination of my ability level in design, the personal world from which I was looking outside, and the information I had about my subjects in advance. Sometimes, these three features could be found in my paintings. I was not supposed to be a professional painter. But, I just wanted to illustrate the emotions circulated among us. My interest in this style of drawing derived from documenting the personal small world that I was living in. It was a world where narrating and disseminating your real thoughts and moods were already prohibited. It was also a place in which protecting my diary from those monitoring it was obsessive and grueling. These paintings were the result of a subtle personal struggle to show that I can go beyond the limits of my existing abilities even in such a complicated situation. A long time later, when all the pages of my small design notebook were scribbled, I felt that once a person is deprived of their personal phone, even in the global information era, they can record their times and places with the simplest tools as it is a need. These recordings might seem primitive, but still, they could respond to my needs. This need was the personal beginning of the process of my imprisonment, and I conceived it intuitively. Later, I changed those thoughts, effects, and motivations into words.

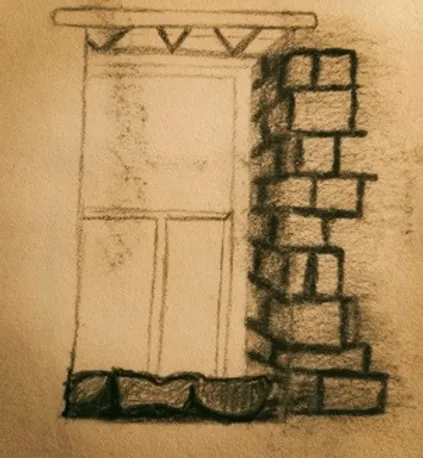

There is a door in the middle of a wall which is approximately one meter and a half above the floor. This door belongs to the Women’s Ward of Evin Prison; a door which is never opened. Inmates use the windowsill to dry green paper and vegetables in the summertime as depicted in the painting. The scorching hot summer sun always blazes down on this side. Prisoners often take their chairs, sitting next to this direct sunshine and absorbing its vitamins into their bodies.

Despite this effective background, my paintings were subjectively drawn in such mundane and tedious ambiance. For me, this work was the product of being drawn into silence and introspection, which was created by the environmental and public pressures of the prison and the frequent wear and tear of the mind of a seeker of solitude on the reality of collective life (which was sometimes desirable and attractive). The atmosphere of life in prison is very tight and dense. One of the resistances is to discover its less imposing or non-imposing layers and make a cocoon around yourself and plant the seed of meaning. Maybe later outside the prison, they will carry greater meanings. Maybe even these new meanings will become a part of your life history, keeping your life outside the prison connected to the starting time and place by continuing to do that work. But pulling a cocoon around yourself and engaging in individual work or producing personal meaning in prison, where collectivism prevails, is not an easy task. Individual activities such as drawing and painting are both the product of loneliness and strengthen it. Maybe that’s why my drawings unconsciously absorbed subjects in such situations. They are the selective reflection of prison, and therefore, they are incomplete to describe the prison’s entire ambiance. Yet, these paintings are one aspect of real life in prison.

Life in prison is more primitive than that of the outside world. Everything seems more precarious and dangerous. Every tool and device that a prisoner has can make her calmer, and losing it causes a lot of anxiety and confusion. Compared to life outside prison, prisoners have a more urgent relationship with things. Therefore, the objects inside the prison reflect the mood and the ambiance of the prison. There is a certain longing in them that belongs to the prisoner, or there is a real power in them with which the prisoner adjusts her daily activities. Among my drawings, those that portray people’s inward feelings and states are simpler than those images depicting people in relation to objects. This is one of the key aspects of daily life in prison. The prisoners’ competition, while being friends with each other, over the acquisition of more things — facilities and services — is an integral part of every prisoner’s life. This competition can be transparently seen in their relations. For example, when meat, as a good source of protein, is being distributed on their plates, you will see how they compete with each other to possess as much as possible. Another example is when they lodge a complaint against each other for getting fresh air, which is a fixed time given to the prisoners with an array of activities to do. These are examples of the relationship between objects and people in prison, which can reflect the life of prisoners in the form of drawings or paintings. My drawings of doors, walls, and bricks reflect an atmosphere of confinement and captivity, which the prisoner is shocked by every now and then.

We can talk about the relationship between paintings/drawings, memories of places, prisons’ particular temporalities, feelings, and prison for a decade or so. I will talk about how I perceive it now. We do not experience prisons every day in the cities. A prison is a specific place. The combination of the feeling of being oppressed, deprived of many rights, and simultaneously, making new friendships, along with the fact that the prisoners personally consider it a temporary experience, make them want to have mementos from this special experience. Once the prisoner is released, the incarceration experience is literally over. However, there is something like a hammer hitting your head and reminding you that this experience was far stronger than other social experiences. The prisoner has long been living her imprisonment, striving to meet her desire and address her issues. This means that she has been constantly relating to her surrounding environment so that she could find a way to survive. The psychological and personal effects of imprisonment do not disappear once the prisoner is released. They linger in the person’s mind, and she knows that she no longer has access to those experiences to readdress those memories etched on her mind. When those experiences are not accessible anymore, the person has to embody them in a way. She has to revive and animate them. We, as prisoners, are aware that our imprisonment would finish, yet its pieces of memory, our relationships with that place, and those affects would not. They will remain in a cycle of oppression and deprivation. We know this matter in prison, so we try to have a memento for the release time. These are precious mementos that we care about, and we want to collect and pass them on to others.

When we are released and time gradually passes, you can see the trace of time in our cumulative experiences. This is a state that we have a sense of while we are spending our incarceration, yet there is no response to how we cannot accumulate them, avoid transforming them into pieces of memory, or stop pondering about the cycle of oppression and deprivation of those people you have left in prison. It takes time for these experiences to become normal so that, like our other social experiences, they lose their significance over time in relation to newer experiences. I believe that it will not happen soon, as there is no experience with the same weight that “imprisonment” has in our daily lives. That is why the memory of prison will be etched on our minds forever and become something unique, abstract, and even sacred. But the more we tend towards this sacredness and/or abstract state in expressing these experiences, the more we stop recognizing its reality. This is a matter of misrepresentation, especially in social media. It can be seen as such in those media representations of prisoners and what happens inside the prison that emphasizes the reflection of individual or collective models of resistance or friendship, which are romanticized to a large extent and ignore other forms of resistance. I would love to end this interview with this: each prisoner has her own memory and memento from prison and my drawings are a part of those pieces of memory and memento. I hope that I could answer your question.

A lot of real movies are broadcast in the prison. Prison guards and inmates are accomplished, inexhaustible, and talented actors in these movies. The ending scene of each movie is similar to those scenes where boxers come back from the court. They come back exhausted of each other or collectively from dealing with “Other ones.” They see around in the room, turning on the DVD player every day, week, and month. They sit at a table and watch the same movie year in and year out.